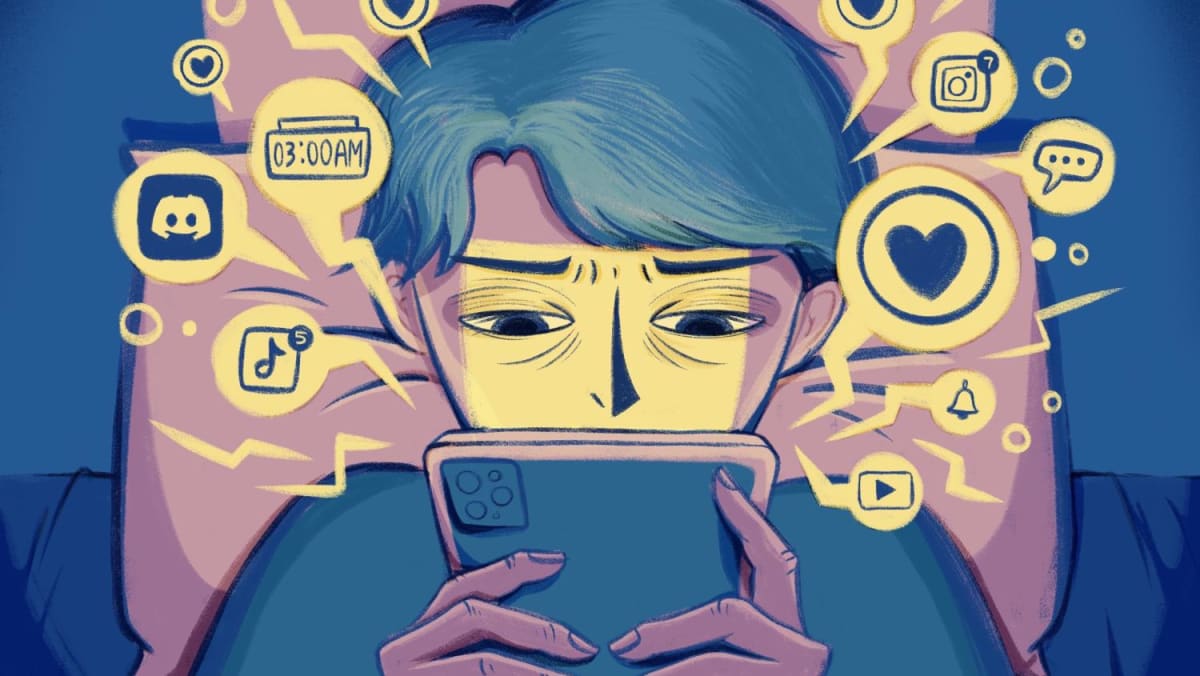

SINGAPORE — Fourteen-year-old student Nadheeruddin Tajuddin spends about four to five hours a day on social media, sometimes till the wee hours of the morning, which leaves him waking up the next day feeling “not that great”.

At times, he even finds himself getting dizzy or sick after consecutive weeks of late-night scrolling. When this happens, he usually stops using social media for a few days, but eventually returns to it.

While Nadheeruddin — who uses mostly TikTok but also spends time on Instagram and Twitter — feels like social media has affected his ability to concentrate in class, he does not plan to get rid of his social media applications completely as he fears becoming “clueless”.

For Secondary 4 student Rebecca Kui, Instagram’s algorithm and infinite scroll feature means that she is constantly fed videos and content that she enjoys. It keeps her entertained for hours, which makes it difficult for her to close the app.

“It’s kinda scary because you begin to neglect your other priorities, and minutes can turn into hours very quickly,” said the 16-year-old, who likens social media to “drugs but under the disguise of entertainment”.

Rebecca also noted how social media has affected her ability to process her emotions, as she can be fed random and vastly different videos consecutively through her TikTok “For You” page.

From being shown a tearful video about a dog passing away, to someone cracking a joke in the next, Rebecca said it was “scary” that she could go from crying to laughing within seconds, as she did not have enough down time between the videos to fully process what she had watched.

Josiah (not his real name), a 17-year-old polytechnic student, used to spend an average of six to seven hours a day on his devices.

While the bulk of this time was spent on gaming, Josiah would also spend three to four hours on YouTube concurrently, watching game footage as he played. He also uses Discord, a messaging app that is popular among members of the gaming community.

His mother, who wanted to be known only as Ms Lisa, told TODAY that at the peak of Josiah’s addiction, he would be on his phone at every waking moment — even during meal times, or while crossing the road.

Josiah would become angry and aggressive when Ms Lisa and her husband tried to take his devices away, she said.

Once, Josiah — who plays sports and is described by his mother as “strong” — even carried Ms Lisa out of the house by her waist, locking her out of their home after she had switched off the Wi-Fi in a bid to get him off his digital devices.

He also began to isolate himself from his family and friends, even declining her offers to take him out for his favourite meal.

While Josiah had always enjoyed gaming from a young age, he became addicted in secondary school.

This addiction worsened during the Covid-19 pandemic, when classes turned online and he was also not able to play the sports he enjoyed outside, said Ms Lisa, a 45-year-old financial coach.

Excessive social media browsing, also known as “doom-scrolling” through Instagram reels and YouTube shorts, may also lead to addiction issues, as adolescents’ developing brains are particularly vulnerable to impulsive, dopamine-driven feedback loops, said Ms Houmayune.

Beyond these, experts warn that the long-term effects of a social media addiction on children and youths’ mental health and development are far-reaching and should not be ignored, even after the addiction has been overcome.

Dr Adrian Loh, a senior consultant psychiatrist from Promises Healthcare, a psychiatric clinic and mental health centre, said: “Addictive behaviours at a young age are definitely a concern.

“Aside from the direct effects, we also find that people who struggle with one addictive behaviour may be vulnerable to other kinds of addictions in the course of growing up.”

This could include a transference of the addiction from one substance or habit to another, such as alcohol, substances, pornography or gambling, he added.

Agreeing, Ms Claire Leong, a counsellor at Sofia Wellness Clinic, said: “This is because addiction is usually a form of maladaptive coping. Until they find healthy coping skills, they are likely to fall into different types of addiction as they experience more stressors in life.”

Experts also warn of the long-term negative impact of such social media addiction.

Dr Ong Say How, a senior consultant and chief of the department of developmental psychiatry at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH), said that existing research findings suggest that a developing child or youth with excessive smartphone use and similar behavioural addiction would not have the opportunity to develop the “essential cognitive capability and emotional skills necessary” to function healthily as an adult later in life.

However, more research is needed to understand this relationship better, he added.

Alluding to the long-term effects of addiction, Mr Narasimman Tivasiha Mani, executive director of non-government organisation Impart where Josiah sought help, said that social media addiction can contribute to anxiety, depression, loneliness, and other mental health problems.

“If left unaddressed, these issues could become more prevalent and severe among the current generation of youths as they grow older,” he said.

“An entire generation struggling with mental health and well-being could place a significant burden on healthcare systems and society as a whole, affecting productivity and overall quality of life.”

‘LEFT OUT’ IF NOT ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Most of the nine teenagers, aged 13 to 18, whom TODAY spoke to acknowledged that being on social media has affected their mental health in varying ways — from skewing their perceptions of beauty, to reducing their attention span, self-esteem, and ability to process emotions.

Only one teenager, 16-year-old Natalie Tan, said that she does not have any social media presence to begin with — though it was not a personal choice, but one mandated by her parents.

“We’re all at the age where (with) our hormones and everything, we’re very prone to comparing ourselves to other people — in the sense that I already compare myself to others in real life, there’s no need for me to compare myself to other people whom I don’t even know online,” said Natalie.

She added that she had seen how her peers compared themselves to images of “women with perfect bodies” on social media.

While not being on social media has been healthy for her in a way, it does make her feel like she is missing out on some things at times.

Natalie said that a lot of conversation topics discussed by her friends tend to start from things they have seen online.

“Because of that, I don’t know what they are talking about, so sometimes I feel a bit left out. I can only sit there and nod, but I have no idea what’s going on.”

For Nadheeruddin, because he uses social media to “check on what’s happening”, he worries that he might become “clueless” if he stops using it completely.

Dr Jeremy Sng, a lecturer at Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) School of Social Sciences, said: “Many studies have claimed to find links between social media use and mental health issues, but the causal direction of these studies is actually unclear.”

It is important to also consider the study’s methodology, as correlation does not always mean causation, he said.

“The effects of social media are very difficult to disentangle, because it’s not that we are only using social media.

“We are also doing a lot of other things — we are going to school, we’re dealing with family, relationships, and all that. So it’s difficult to pinpoint that something has happened solely because of social media.”

Dr Loh from Promises Healthcare added: “For social media, it has been around for barely past a decade, so we are still trying to understand downstream implications.”

SIGNS OF A SOCIAL MEDIA ADDICT

When does social media consumption morph into social media addiction?

To this, Ms Jane Goh, deputy director of creative and youth services at the Singapore Association for Mental Health, said: “As a simple rule of thumb, if you find yourself constantly refreshing your social media applications and chasing validation and likes online, or posting to garner attention, then it could be time to reevaluate your social media habits.”

Experts also say that the long hours spent on Instagram, TikTok and the like may not necessarily be a sign of such an addiction. Instead, a good gauge of whether one’s social media use has become problematic is when it starts to displace other activities.

“Healthy social media use may look different for each person,” said Ms Leong from Sofia Wellness Clinic.

“Before I would call any behaviour an ‘addiction’, I look at three different factors — tolerance, dependency, and dysfunction,” she said.

Dr Ong of IMH added that for symptoms to be pathological, it must affect the person’s daily functioning, which could include avoiding school, giving up social gatherings, or experiencing mood swings.

“When all these things break down, that is when it’s a sign that it’s more than just a hobby. It’s a sign of an addiction.

“If a young person spends many hours on social media but still makes time to meet friends and have perfect relationships, including doing well in school, eating well and sleeping well, then in the eyes of the person and the clinician, it might not be considered a problem,” he said.

Mr Mark Rozario, a clinical psychologist at Mind What Matters, added that while the disruption of one’s daily routine or schedule can be a clear sign of risk, another signal is if one is also spending more time on social media than initially planned.

“Youths may not identify it themselves, so it could also be their peers, siblings, (or) close ones who point it out,” he added.

Regardless, addiction is a progressive illness with increasing severity of symptoms, said Ms Pang of Visions by Promises.

“Instead of focusing on whether or not there is an addiction before seeking help, early intervention is encouraged. In this regard, it would be helpful to look for signs of mood changes, changes in self-care habits, or difficulty in self-regulation when there is an interruption to use,” she added.

Collapse to view Expand to view

‘EMPOWERING’ YOUTHS TO ESTABLISH BOUNDARIES

Since there is no escaping from a rapidly digitalising world, parents, professionals, policymakers and social media companies alike will have to navigate the myriad challenges, alongside children and youths’ exposure to, and use of, the various platforms, experts told TODAY.

To protect Singaporeans from harmful online content, Parliament passed a law in November which empowers the authorities to issue directions to online communication services to ensure local users are protected from content such as sexual violence and terrorism.

Providers who fail to comply with these directions could be subjected to fines of up to S$1 million.

To minimise the damage that social media could do to young people, Dr Murthy, the US Surgeon General, said in his report that parents and caregivers can create a family media plan which sets technology boundaries at home, create tech-free zones and report problematic content and activity.

Ms Jane Goh, deputy director of creative and youth services at the Singapore Association for Mental Health (SAMH), said that educating the young on social media use would be the way to go.

“While preventing the use of social media would seem like a simple solution, it would also create a feeling of isolation from their peers, creating a feeling of Fear Of Missing Out (Fomo),” said Ms Goh, echoing the sentiments of youths like Nadheeruddin and Natalie.

Agreeing, Ms Nicole Pang, who is head of mental health care at Impart, said that managing social media use is not solely about limiting the amount of time spent, but in empowering youths to establish their boundaries and make active decisions on the kind of content they would like to engage in or not interact with.

Ms Tham of We Care Community Services said that to prevent an over-dependence on digital use, parents may also prioritise introducing non-digital-based activities in their child’s formative years.

This includes encouraging outdoor activities and sports, especially those that involve group and in-person social interaction, teamwork and collaboration.

Rebecca’s father, Mr Kui Tuck Meng, 62, said: “We are at the age where we need to allow our children to use all these social media for their social interactions, which have their good side, as long as they are able to control its usage and are discerning to access and avoid bad social media postings.”

In turn, Rebecca said that teens like herself are still forming their world view and will require some form of guidance.

“Hence, although I think we’re capable of managing our social media usage, parents should still check in and remind their children to strike a balance between social media and their offline lives.”

Mr Brucely Christopher Edison, who has two sons aged 18 and 20, noted that with mobile phones becoming a necessity, it is hard to control what children use them for.

“For me, I think it’s almost virtually impossible to control them, because the moment you give them a phone, it’s an open channel and they are able to set up (social media) accounts,” said the 49-year-old business-owner.

He added that if parents were aware of what their children did on social media, they would be able to pick up on instances when their children were influenced and “bring them back”.