SINGAPORE — At the Queenstown Public Library, Mrs Diane Tan watched on as her 22-month-old daughter pulled book after book out of its mahogany shelves, flipping through the pages enthusiastically.

The unassuming two-storey establishment along Margaret Drive, with its pearl-grey exterior lined with bowtie motifs, is Singapore’s first-ever neighbourhood library and turns 53 in April next year.

The building might not appear to be a place a child would pine for, but on the rare days when it is closed — the library is open seven days a week except on public holidays — Mrs Tan said it is as if her daughter’s “favourite toy has been taken away”.

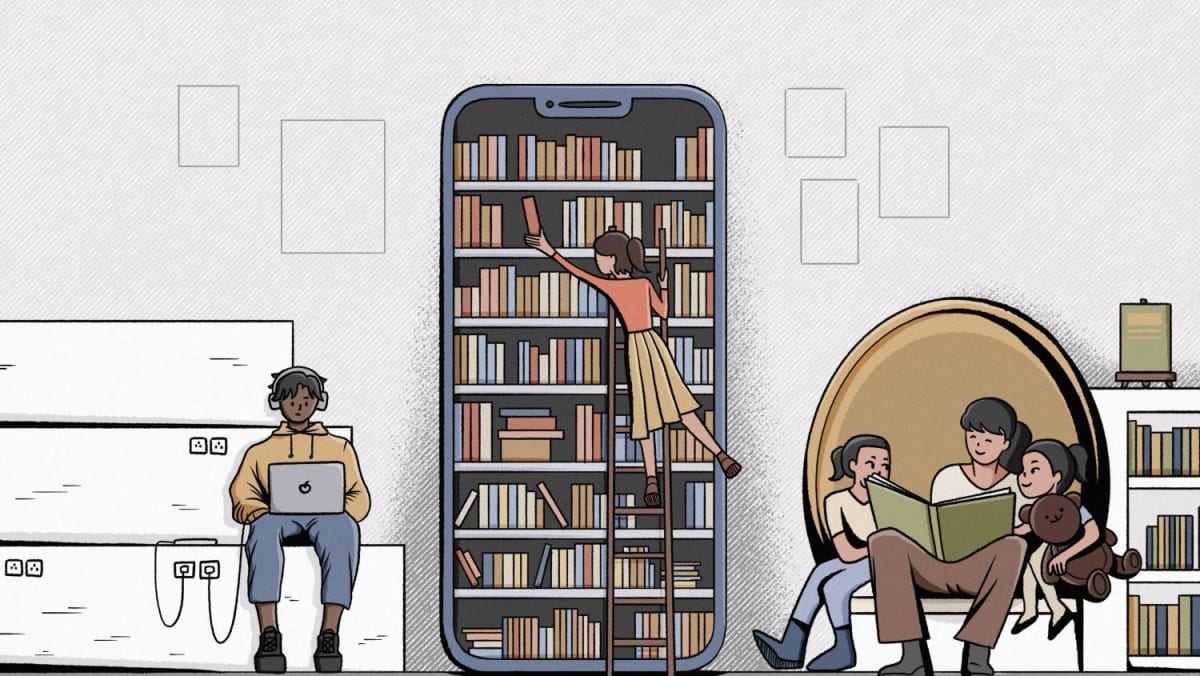

Even in a digital world where information is readily accessible at one’s fingertips at any given moment, the public library does not seem to have lost its relevance to Singaporeans both young and old.

Mr Marcus Loh, a 40-year-old who has been a frequent library goer for decades, said that its draw is as a space “deliberately designed” for one to read books comfortably.

“If you can spend two hours in a bookstore, then you can easily spend four hours in a library,” said Mr Loh, the director and head of strategic communication of digital transformation consultancy Temus.

Mr Loh’s habit of visiting public libraries has continued to this day despite his busy schedule and his acknowledgement that it would be easier to read on his smartphone. But he believes that the library is “a better search engine”, because he can access rare books no longer in print.

In addition to the National Archives of Singapore, the National Library Board (NLB) currently manages a network of 28 libraries — including the five-storey Punggol Regional Library, the newest library which opened in April this year.

Earlier this year, the library@esplanade closed its doors for good, with its collections and programmes to be moved to the National Library Building along Victoria Street, which houses the Central Public Library and the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library. The Central Public Library and Marine Parade Public Library are temporarily closed for renovations.

Nevertheless, the NLB also announced last month that the Bukit Batok Public Library will double in size as part of the board’s ongoing efforts to systematically rejuvenate existing libraries, with the Queenstown Public Library also slated for a revamp in the near future.

The NLB said in a media release on Nov 17 that as of August, 78 per cent of Singapore residents visited NLB’s libraries and archives and accessed its content in the preceding year.

This was up from 61.7 per cent in 2022, and 72.5 per cent in 2019 before Covid-19 struck.

In response to TODAY’s queries on public libraries’ visitorship, the NLB said that that it saw a total of 16.5 million visits in 2022 across its network of libraries, the National Archives of Singapore building at Canning Rise and the Former Ford Factory — an increase of 43.5 per cent, or 5 million, from 2021.

The Former Ford Factory along Upper Bukit Timah Road is managed by the National Archives of Singapore and houses a permanent World War II exhibition.

Library-goers agree, adding that the “magic” and other perks of being present in a physical library remain strong “pull” factors for those who visit frequently.

“I love browsing the shelves. It’s wonderful to stumble on a title or author unexpectedly — it’s the promise of a lovely surprise, almost a serendipity,” said Mr Kon, the NTU senior lecturer.

This element of unpredictability is what makes a library special, said 27-year-old entrepreneur Muhammad Firdaus Syazwani, who used to visit the library regularly as a polytechnic student. Since he started work, he visits the library less often.

“If I wanted to read something interesting but I didn’t know what, I can just browse the different sections, read the synopsis or a few chapters. If I like it, I borrow it,” he said.

Mr Firdaus, whose professional expertise lies in search-engine optimisation (SEO), added that the internet might not be the best place to discover new authors and books that you like, because results on search engines can be “skewed”.

“Authors with marketing teams and titles frequently touted would come up more often. So even if there’s a book out there for you, if it isn’t mentioned frequently, it’s not going to rank high on search,” he said.

LIBRARIES’ ROLE AND THEIR EVOLVING PHYSICAL SPACES

Around two decades ago, the value proposition of a library was that it provided people with the world’s information — fiction and otherwise — through the medium of books, said non-library goer Martin Layar, a management trainee in the shipping industry.

As digitalisation becomes part and parcel of daily life, the 26-year-old said he does not see the point in paying a visit to the library anymore.

But others told TODAY that public libraries’ role has evolved beyond being mainly repositories of books.

Its physical spaces are also changing to meet another need — to help people engage with information on a deeper level, said Ms Shameem Nilofar Maideen, university librarian at the Singapore Management University (SMU).

In a similar vein, NLB’s director for planning and development Wan Wee Pin told CNA in August that the board does not want libraries to be places solely for reading anymore and its mission has evolved into one “of getting people to learn” — which can be through other means apart from reading.

Indeed, Singapore’s libraries of today look nothing like they did in decades past.

On the fourth floor of the new Punggol Regional Library for example, there is a dedicated space for library users to try their hand at fabrication technologies such as 3D printing and robotics, under an initiative called MakeIT at Libraries.

Just a few steps away is Launch, a business resource centre for aspiring entrepreneurs, microbusinesses and gig workers, complete with a meeting pod where patrons can consult with a start-up specialist during office hours.

If one were to take a brief walk around the rest of the Punggol library, the large walkways and spaces between aisles soon become apparent, so does the accessible nature of just about every facility.

There are wheelchair ramps to enter meeting booths, printing stations with high contrast large-key keyboards and even private spaces known as “calm pods” for patrons to self-soothe.

According to NLB, these features were put in place to fulfil part of the role it sees itself playing as an “equaliser” to society, where everyone feels welcome within its spaces.

Libraries also have the potential to use their physical spaces to “open up” information and package them in different ways, to suit the learning style of different learners, said Ms Shameem, SMU’s university librarian.

To cultivate a love for reading among young children, the NLB has ramped up the number of programmes for them in recent years.

It introduced the “Babies Can Be Members Too!” programme in 2016 to encourage bonding between parent and child through reading from an early age. Under the programme, parents can register their babies as library members and receive a gift pack comprising children’s books.

Then in 2020, the NLB launched “The Little Book Box”, a monthly subscription service in which eight curated books for children would be delivered to one’s home at a fee of S$10.80 a month. Since its launch in November 2020, the service has delivered more than 300,000 children’s books.

But perhaps its most ambitious and successful initiative geared towards children is “Book Bugs”, a bug-themed collectible card game to encourage reading in both English and Mother Tongue languages.

Children can borrow any library item or complete monthly quizzes to earn points, which can then be exchanged for collectible cards featuring unique bug characters — each with its own personality trait and lore inspired by books in Singapore’s national languages.

Since its inception in 2016, Book Bugs has been through four iterations, the latest of which in 2022 saw over 90,000 unique patrons redeem more than 2 million Book Bugs cards at public libraries. This contributed to over 10 million English and Mother Tongue book loans, the NLB said, adding that it would embark on its fifth iteration due to popular demand.

LOOKING FORWARD

While many libraries overseas are struggling to survive, those interviewed by TODAY believe that the public libraries in Singapore would continue to have an important place in society — with advancements in technology helping the libraries to adapt to the new needs of users.

SMU’s university librarian Ms Shameem said: “When you look at the conflicts of society today and in the future, it’s not going to be determined purely by your military might… battles are being waged across digital screens.”

“That’s why being an information literate person who can critically engage with information on a deeper level is going to be a definite advantage in a complex world,” she said.

Beyond the public libraries, some academic libraries in Singapore have also made drastic changes to its operations to keep up with the times.

The Tay Eng Soon Library at the Singapore Institute of Management (SIM) last year became a “shelf-less” library to free up space for more collaborative purposes once occupied by shelves of physical books.

“The library is no longer just a space for self-study, it’s for discussion, for you to share knowledge,” said Mr Chuah Yeow Seng, SIM’s senior head of campus infrastructure and operations.

Its students may only pick out books they want via an app, after which its school librarians would collect and place them in designated collection points.